در روزهای بیستم و بیست و یکم مارس سال آتی میلادی، کارگاهی با عنوان «پویائی حرفهای در سرزمینهای اسلامی (۹۰۰-۱۶۰۰م.): علما، ادبا و دبیران»، در کتابخانه ملی فرانسه واقع در شهر پاریس برگزار میگردد. علاقهمندان به شرکت در این کارگاه میباید چکیده مقاله خود را حداکثر تا نیمه ماه سپتامبر سال جاری میلادی، به این کارگاه ارسال نمایند.

Professional Mobility in the Islamic Lands (900-1600):

ʿulamāʾ, udabāʾ, and administrators.

March 20-21, 2019

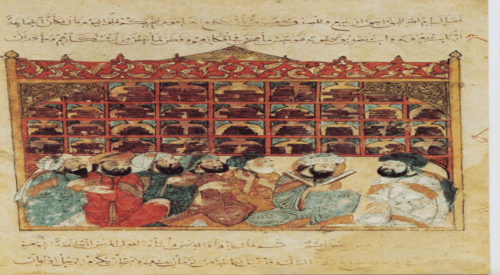

One of the Maqāmat of Abū Muḥammad al-Qāsim b. ʿAlī al-Ḥarīrī illustrated by Yaḥyā b. Maḥmūd al-Wāsitī, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, ms. arabe 5847 (first half of the 13th century/Irak)

Adherence into the social-cum-cultural group of ʿulamāʾwas relatively open and depended oftenon personal scholarly accomplishment, while other considerations like social, ethnic, or geographical origin played a lesser role. On the other hand, the professional mobility of the ʿulamāand advancement opportunities within this group for religious, legal, administrative, and political appointments depended to some extent on social networks and, in some cases, on adherence to certain families or madhhabs.This professional mobility will be the focus of this two-day workshop.

Joan E. Gilbert argued that Zangid and Ayyubid Damascus (12th-13th century) witnessed the beginning of the professionalisation and bureaucratisation of the ʿulamāʾ.This trend increased under the Mamluks. Other scholars including I. Lapidus, M. Chamberlain, J. Berkey, C. Petry, D. Littleand B. Shoshan treated the major role played by the Mamluk periodʿulamāʾinmanipulating knowledge transfer for social capital and to acquire administrative and political offices within a society that was open to a widespread mobility. Recently, scholars like I. Perho showed that while individual merits played an important role in the professional mobility, lineage and networks were also factors of social advancement.

Between the rise of the madrasas under the Saljūqs and the incorporation of the education system into the Ottomans state, the scholarly elite increasingly monopolised the religious and administrative appointments often with the tacit or expressed consent of political authorities especially under the Mamluks but similarly under other Islamic empires. Within this context of the Middle period of Islam,there is a need to further understand the professional mobility of theʿulamāʾ.Such enquiry should take into account the processes of gradual professionalisation, institutionalisation, and the adabisation of the ʿulamāʾin the long period between the Saljūqs and the Ottomans.

The aim of this workshop is to reflect on the professional mobility of the ʿulamāʾalong spatial, horizontal and vertical axes. Vertical mobility is understood here as the process within which ʿulamāʾmoved upwards in various paid jobs, including the positions of imām, khaṭīb(preacher), mudarris/shaykh (teacher), qāḍī(judge), qāḍī al-quḍāt(chief judge), and others. Horizontal mobility denotes how the ʿulamāʾserved as salariedadministratorsof religious or administrative offices. This includes jobs like the chief Sufi (shaykh al-shuyūkh), muḥtasib(market inspector), nāẓir al-awqaf(supervisor of charitable endowments) and, moreover, non-religious administrative including, for instance, nāẓirbayt al-māl (superintendent of the treasury), diplomatic emissary, and various appointments in the chancery.Horizontal mobility furthermore, intersects with the notion of adabised scholars since many ʿulamāʾwere poets and belletrists.Spatial mobility investigates the traveling ʿulamāʾnot as much as émigrés but as professionals who, due to new placements, moved both ways between Damascus and Cairo, Khurāsān and Anatolia, Central Asia and Syria, the Mashriqand the Maghrib, Sicily and the Eastern Mediterranean, India and the Hijāz, or other axes of mobility.

This workshop is interested in papers that consider the following questions: How and when did themadrasasstart producing bureaucrats?What did getting close to political authority entail for the ʿulamāʾ? How did offers for higher appointments travel in Islamic lands? How did the competition between ruling elites and households impact this professional mobility? Was this mobility controlled by households and governments or by the ʿulamāʾthemselves? How did the uniformity ordiversity of madhhabsimpact this mobility and the opportunities available to the ʿulamāʾ? Which ʿālimsepitomised this mobility more than others? Was this mobility more common under certain dynasties and regimes?

Paper Submission

-Please send by September 15, 2018 an abstract of 300 words or less and a CV to SOASconference@gmail.com

-Papers may be presented in English or French.

-Presentations should not exceed 25 minutes.

-Applicants will be notified of the status of their proposals by November 30, 2018.

Information

This workshop is co-organised by Mohamed El-Merheb (School of Oriental and African Studies, SOAS) and Mehdi Berriah (Paris 1 La Sorbonne University/University of Grenoble-Alpes).

Any queries about the conference can be directed to: SOASconference@gmail.com

Location

SOAS University of London

Thornhaugh Street

Russell Square

London WC1H 0XG

United Kingdom